The following is a Guest Post by Meyli Chapin.

In 2019, I was on a business trip in Kenya when Al Shabaab terrorists attacked the hotel I was staying in. For seventeen long hours, I hid and cried and said my goodbyes over text as I listened to the explosions and gunshots going off all around me.

When the good guys knocked on my door and extracted me from the property the next day, officially alive, I was incredulous. This terrible thing that had nearly taken everything from me had released me from its grasp. It was finally over.

Except that it wasn’t.

Yes, I was physically safe again. But all of that waiting, that wondering, that listening to explosions, that mental imagery I had seen of myself being violently killed in my hotel room, it didn’t just go away. It stayed with me and haunted me, at night when I tried to sleep, during the day when I went to hug my family. It was always there with me in the back of my head.

I started to suffer from panic attacks, nightmares, insomnia. I was terrified to leave my house. I was incredibly on edge, and would yell at my loved ones no matter how helpful or patient they were being. I felt like at any minute I would be back in another attack, my life hanging in the balance once again. I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t focus, I wasn’t myself. And worst of all, I didn’t understand what was happening. I had lived, I had gotten through the attack physically unscathed, so what was wrong with me? I had no excuse for feeling so terrible. In fact, I felt like I didn’t ‘deserve’ to struggle; I hadn’t even come face-to-face with the terrorists.

Luckily, I had an amazing support system, so before I knew it I was in the care of a talented trauma therapist. She diagnosed me with PTSD, and explained three things that changed my life. First, PTSD is not something that only military personnel experience. It can affect anyone who has been through something terrible. Second, no two people will experience a trauma the same way. That’s why post-traumatic stress is a spectrum. A person’s reaction to a difficult situation has to do with their genetics, biology, life experience, previous history of trauma, etc., so there is no way to predict or designate the people who are most likely to struggle after trauma. And finally, every second I had spent in that attack had genuinely altered the chemistry of my brain. I had gotten used to being on edge, being extremely alert, being afraid for my life. My brain was wired for danger on a constant basis, and we had to work to rewire the neural pathways by teaching my brain that I was once again safe and it could turn off fight-or-flight mode.

After many months of therapy, I walked out on my last day PTSD-free. It was some of the hardest work of my life, and it taught me that the mental fallout from a trauma can be as harrowing as the trauma itself. But it made a world of difference: it restored my ability – and desire – to live my life.

Shortly after I finished therapy, the pandemic started, and I found the parallels between COVID and my experience striking. The virus added a constant burden to every moment, a heightened stress and anxiety, a deep fear of the unknown, of the future, until that became almost normal. Our brains dialed up our ambient levels of concern, and our neural pathways were altered to be more on edge. All around me, I was seeing a complete denial of the severity of the fallout. Friends and loved ones – regardless of the fact that some were frontline workers, some had lost family members to COVID, some were high risk themselves – all said they didn’t ‘deserve’ to be struggling under the massive weight of the pandemic. Even in this denial, they reminded me of myself after the attack.

At the end of 2020, the CDC conducted a study of 5,000 American adults. They found that over a quarter were expressing symptoms that were trauma- or stressor-induced. If you generalize that to the full population, that would be over fifty million adults in the US, which is more than the total number of Hulu subscribers.

This pandemic, whether we admit it or not, has been immensely trying. It has affected our neurochemistry, and will continue to affect how we think and respond to our environment long after it’s over. We need to understand that our identities have inherently changed: we are all now survivors. And, as ironic as it sounds, we have to be cognizant of the fact that sometimes it can be hard to survive surviving.

That is exactly why I created Trauma Brace for iOS. With more demand for mental healthcare than ever, we are in desperate need of more creative, affordable and accessible solutions that still rely on the tried and true evidence-based methods that we know actually work. With Brace, I wanted to provide the type of topline treatment I received, but in a self-help modality so that users can help themselves heal on their own time, in their own homes, at a tiny fraction of the cost. What’s even better is that Brace does not require an official PTSD diagnosis, and can be used as a bridge to therapy, as an add-on to therapy, or as a standalone self-help solution. Not to mention, we are committed to the highest level of privacy and security, so not only is all personal information stored on-device, but Brace is also fully HIPAA compliant. So if you are struggling to process a traumatic experience, and you don’t have access to therapy for whatever reason, give Brace a try. I hope it can help you get some much-needed relief.

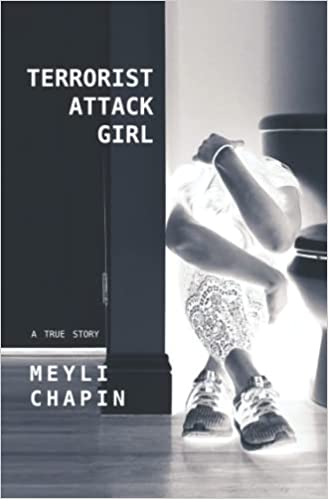

Meyli Chapin is the CEO and Founder of an international trauma treatment company. Her memoir about surviving terrorism and PTSD, Terrorist Attack Girl, is now available on Amazon and Audible.